“A party of Vicars Choral and Exeter Gentlemen”

The Royal Subscription Rooms, Exeter, the location of the choir’s first performance in 1847 (Image supplied through ‘Exeter Memories’ by kind permission of David Cornforth)

Around a decade before the formation of the Exeter Oratorio Society, Exeter had been struck by a serious outbreak of cholera. The first victim of the disease was a mother (with two sick children) living in North Street. By the time the outbreak had been contained, there had been 1,200 cases and 402 fatalities. A young medical doctor, Thomas Shapter, offered his services to the Board of Health, working tirelessly with those affected but also recording and mapping the impact of the disease and the insanitary living conditions on which it thrived. In an Open Letter to Exeter’s Lord Mayor, Shapter speculated that “lack of ventilation, overcrowding and squalor” were to blame, with his voice contributing to the clamour for the adoption of new public health legislation in 1848.

Thomas Shapter’s cholera map of Exeter, 1832 (Engraving by Risdon, Lith., Exeter in

Shapter, Thomas History of the Cholera in Exeter 1832 John Churchill, 1849)

Dr Thomas Shapter, eminent physician and member of EOS (Portrait of Thomas Shapter

in the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital, Wellcome Gallery, London, artist unknown)

Among the ranks of the basses was Dr Thomas Shapter, newly appointed as a physician at the Devon & Exeter Hospital and about to publish his acclaimed book on the Exeter cholera outbreak. Joining the alto voices was W. Denis Moore, the Lord Mayor of Exeter, whose presence, The Western Times reported, was greeted with “hearty and protracted applause”.

However, on 20 May 1847, the Committee reported that “a communication had been received from the Right Worshipful the Lord Mayor requesting that a second performance of the Messiah might be given for the purpose of increasing the funds now in collection for the relief of the poor.” The Committee duly agreed and arranged a second performance on the same basis as before. At a General Meeting of the Society after the concert, on 1 July, there was a marked change of mood. It was “Resolved – That the balance of £39.00 be paid to the Treasurer of the Relief Fund” (worth around £5,000 at 2024 prices). Parting with this amount of money was clearly a painful experience and the meeting added a rider: “That in future no performances were to be given on behalf of any charities.”

The following year Dr Thomas Shapter himself became Lord Mayor and relations between the EOS and Exeter’s mayoralty seem to have improved. For many years, Dr Shapter played a considerable part in the life of the Society, which resumed the practice of performing for charity.

Discordant notes

By 1850, there were signs that some of the EOS’s early enthusiasm was being tempered by reality. Handel’s Messiah remained a standard part of the repertoire, though Haydn’s Creation was selected for the spring public performance in 1849. While the Annual Report the next year reported that the Messiah choruses were performed by the Society’s choir “with a better observance of light and shade than hitherto”, the Committee impressed on the membership the importance of regular attendance at rehearsals. Only by “regular and simultaneous practice” could the choir hope to develop a full understanding of the compositions. As it was, the Committee considered that “there is wanting a greater power of expression, a better observance of the various gradations of tone, and distinct pronunciation of the words – all necessary to the clear effectual development of the Composer’s meaning.”

The Committee acknowledged that the membership was pressing to perform works by Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Mendelssohn and Spohr but warned that “although much has been done, still they cannot but feel that a great advance must take place before the works of these Writers can be attempted with success.”

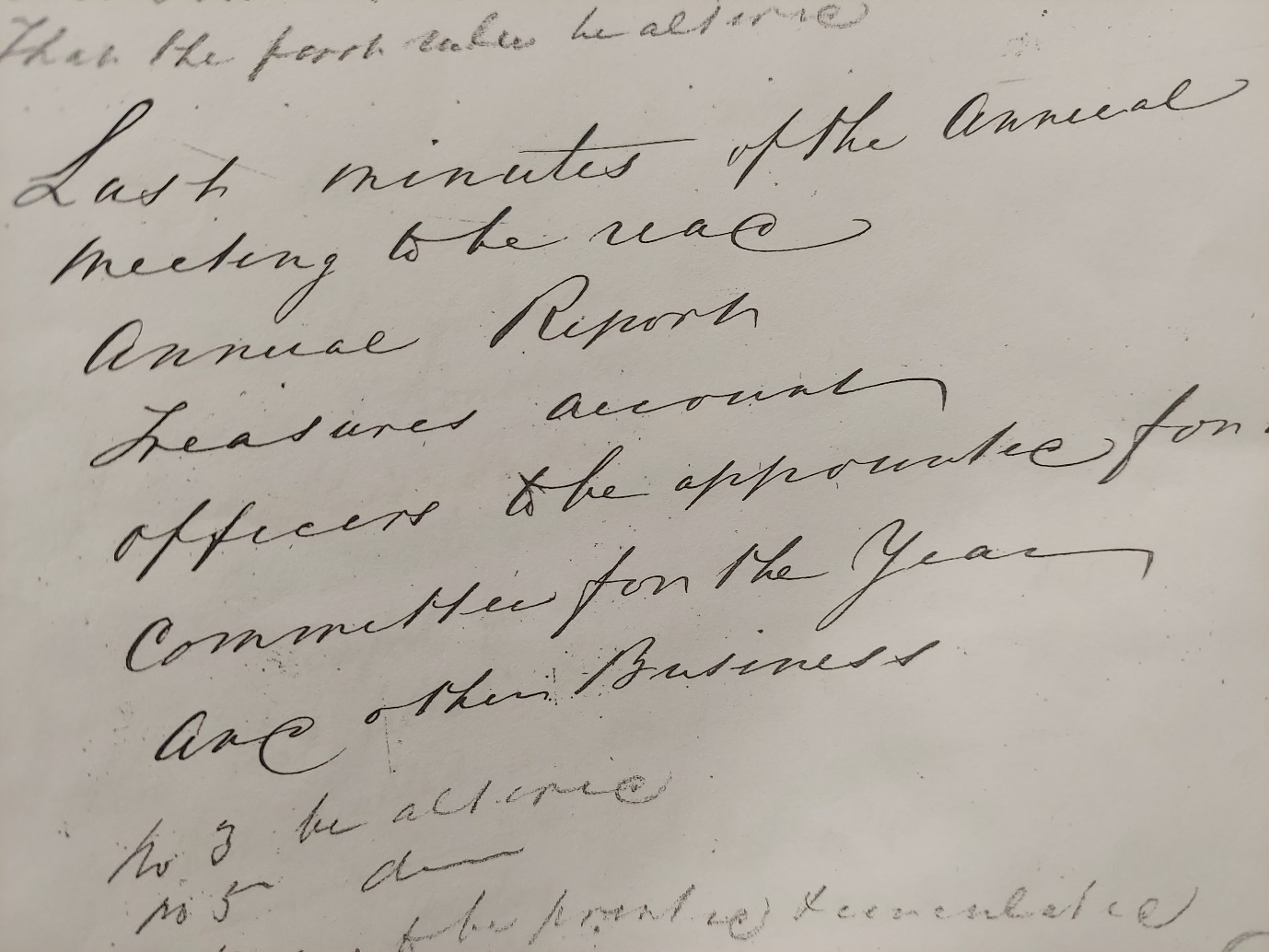

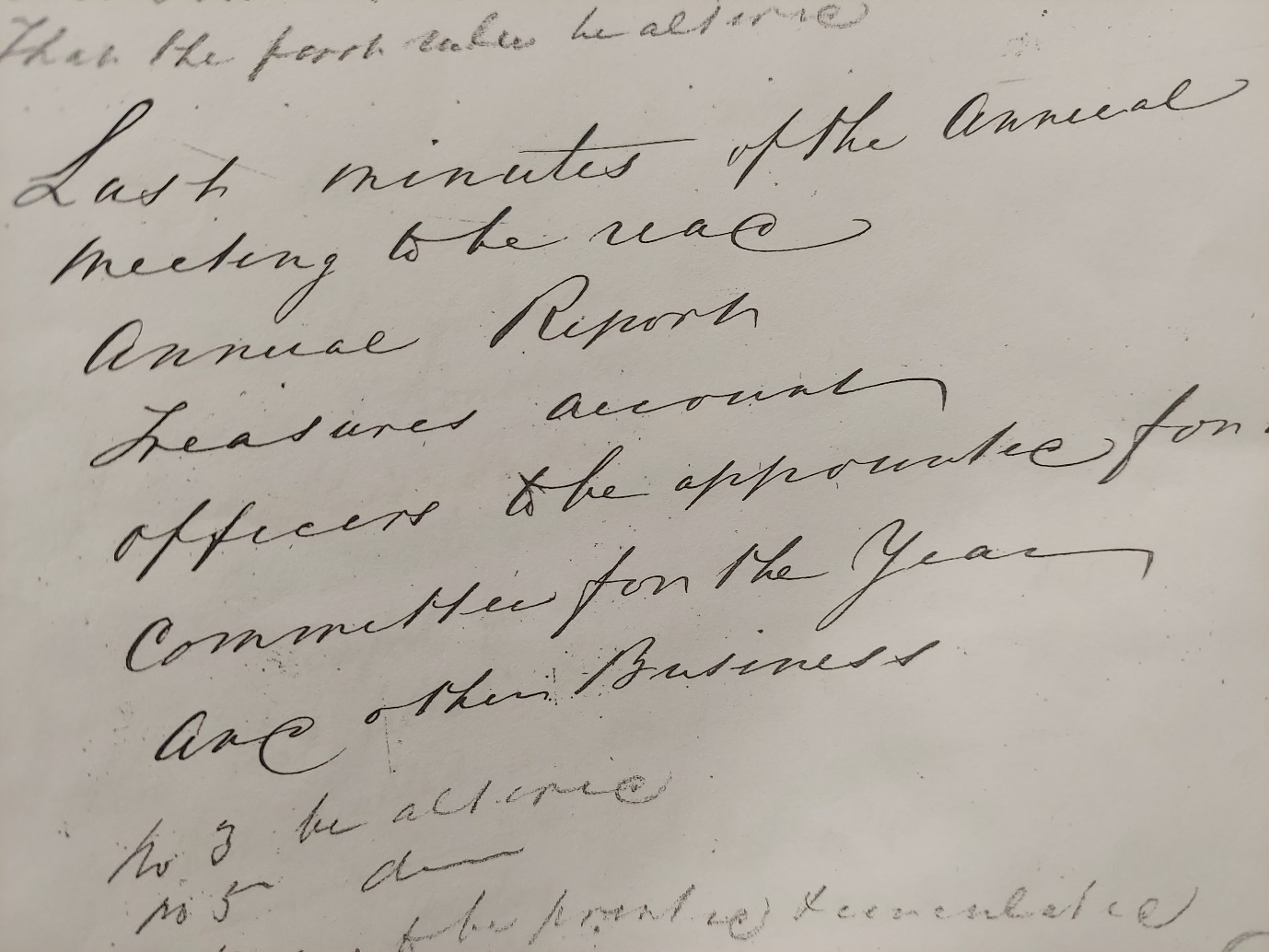

An extract from the Minute Book, 1850 [Devon Heritage Centre, Devon archives:

Exeter Oratorio Society. Minute Book 1846 – 1859, 219/48/4)

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A new monarch – and a new century

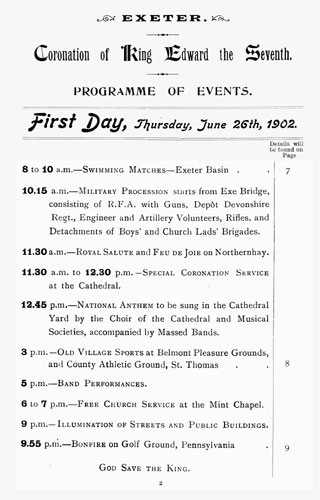

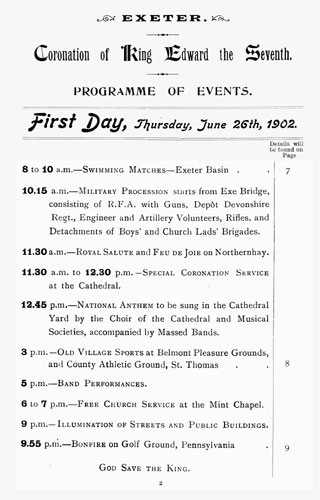

By the turn of the century, the Exeter Oratorio Society had successfully navigated its first fifty years and was an established part of musical life in Exeter. In 1901, Queen Victoria died at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight at the age of eighty-one, having reigned for sixty-three years (longer than any of her predecessors). Her eldest son “Bertie” at last succeeded to the throne as Edward VII. His coronation in 1902 was widely celebrated, including in Exeter where the “musical societies”, as the programme records, played their part in the festivities.

The Exeter Coronation celebrations, 1902 (first day)

Image supplied through 'Exeter Memories' by kind permission of David Cornforth

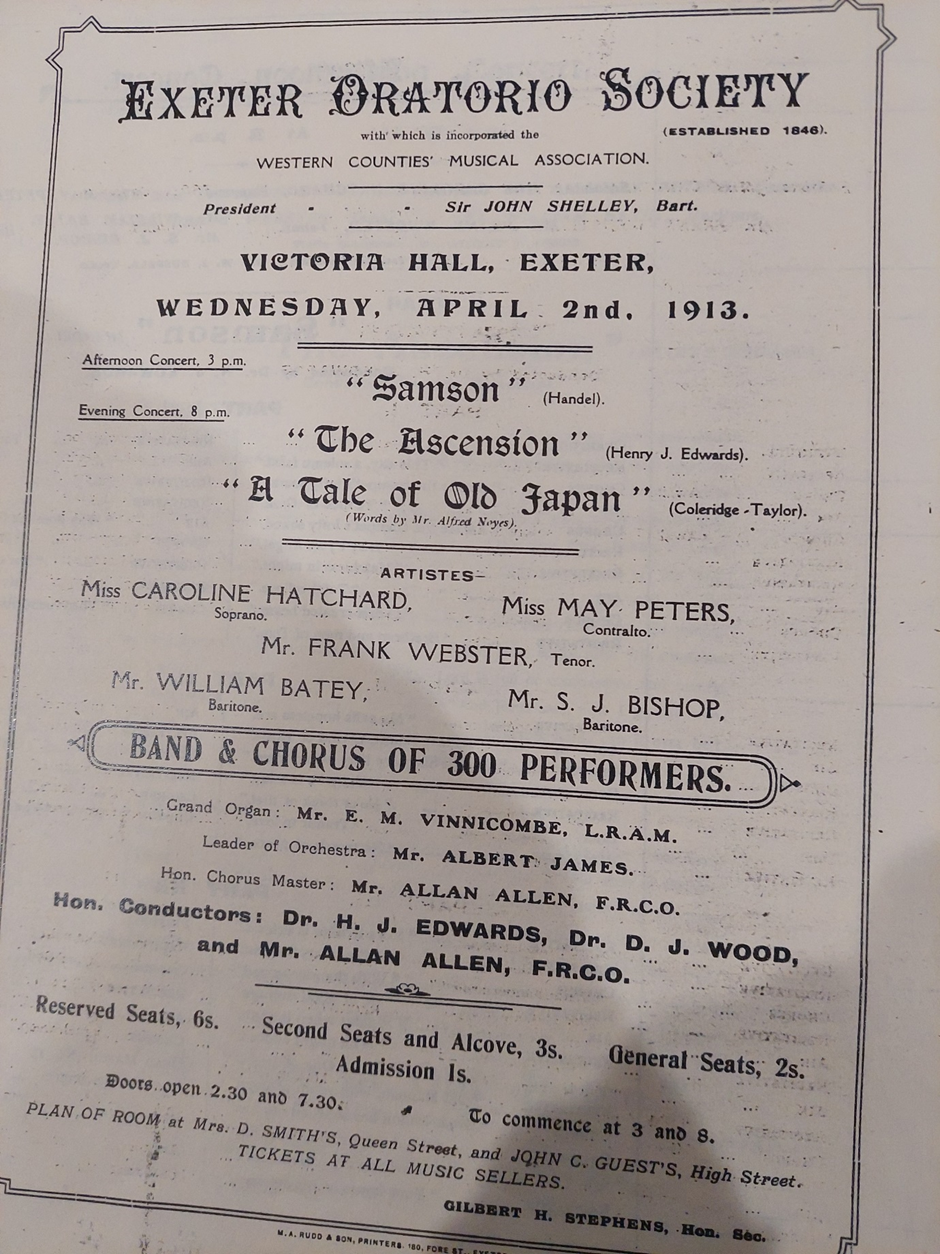

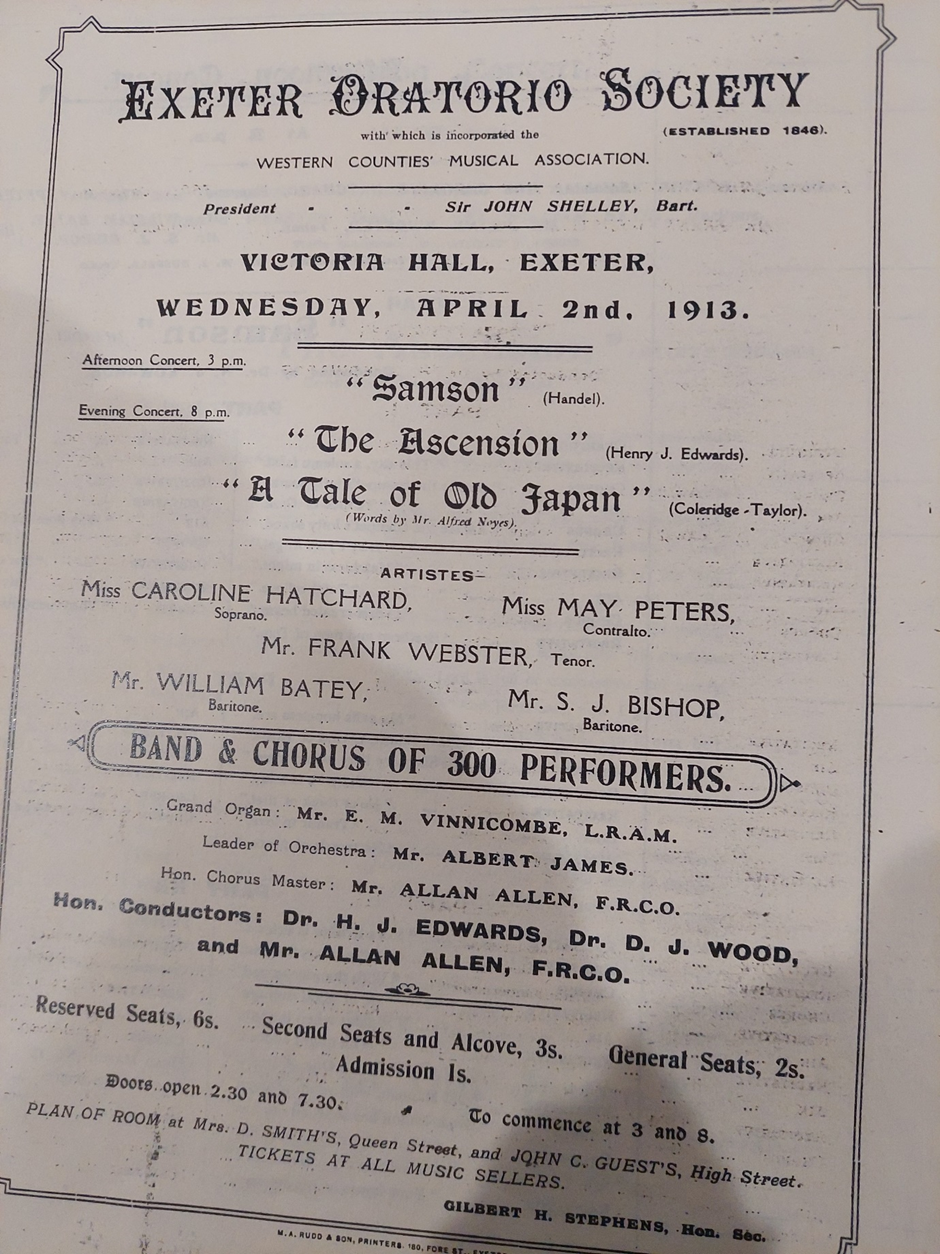

In 1906, the Society marked its first sixty years with the publication of a commemorative booklet. A year later it merged with the Western Counties Musical Association, appointing joint conductors until 1919. In 1913, in the Victoria Hall, the society performed Handel’s Samson in the afternoon, and H. J. Edward’s Ascension and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s A Tale of Old Japan in the evening. Performing twice in a day, and presenting separate repertoires, was a common pattern at the time but must have been challenging, both physically and technically.

EOS programme for April 1913 concerts (Archive of Exeter Philharmonic Choir)

Caroline Hatchard at Exeter

Prominent among the soloists for the two concerts on 2 April 1913 was the celebrated soprano, Miss Caroline Hatchard. Aged thirty, she was approaching the height of her powers. (For more about Caroline Hatchard, click here).

The Great War comes to Exeter

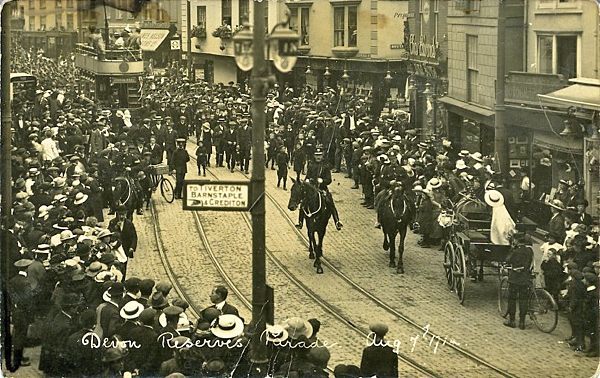

On 4 August 1914, Great Britain was at war, the news breaking in Exeter from the offices of The Western Times in the High Street. The improbable spark to what became a world-wide conflagration was the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, together with his wife, in Sarajevo. The interlocking alliances of the great powers, which were supposed to guarantee peace, instead made war inevitable. Two days later, one of the first official fatalities of ‘The Great War’ was Stoker Henry Copland, from Topsham. He was killed when his ship, HMS Amphion, struck a German mine in the Thames estuary and quickly sank, with much loss of life.

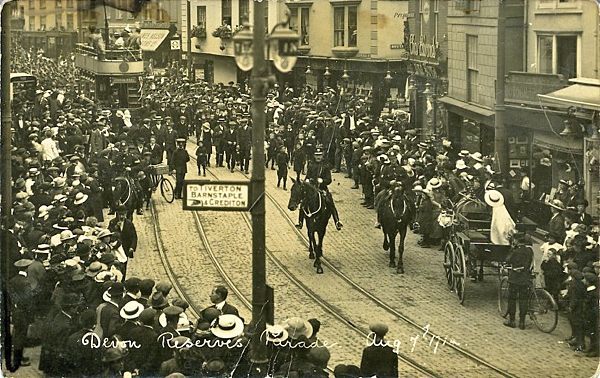

The Devon Reserves parade down Exeter High Street, 7 August 1914

(Image supplied through ‘Exeter Memories’ by kind permission of David Cornforth)

Amid great patriotic fervour, reservists and territorials were mobilised and many answered Field Marshal Kitchener’s appeal to join the colours as he built new volunteer forces to augment Britain’s small professional army. Commonwealth forces also began to pass through Exeter on their way to France and other battlefields. By Christmas 1914, the festivities at home continued much as before, with “Mother Goose” the pantomime at the Theatre Royal. The Exeter Oratorio Society had selected Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius as the highlight of its 1914 festival but “having regard to the War they were reluctantly compelled to postpone its performance”. Nevertheless, EOS’s concerts continued throughout hostilities, though The Gazette reported that “they had suffered somewhat by the depletion in the ranks of male voices”.

By 1916, two major battles – one at sea and one at land – saw many from Exeter and Devon featuring on the casualty lists. At the Battle of Jutland, which narrowly confirmed

Britain’s naval supremacy, twenty-six sailors from Exeter died in battle. The youngest was Aaron Balson, of Bartholomew Street, Exeter, who was just eighteen.

A month after Jutland, British and Commonwealth forces, together with the French Army, launched a major offensive which became known as the Battle of the Somme. At the end of the first day, allied forces had sustained 57,000 casualties, with nearly 20,000 killed. Of the dead, twenty-two were from Exeter. Only modest advances in the frontline were achieved over four months of fighting.

The mounting death toll showed itself in numerous personal tragedies and broken families. The new Bishop of Exeter, Lord William Gascoyne-Cecil, took office in December 1916. By then, he had already lost one of his four sons, aged twenty, at Ypres the year before. Two more of his sons were to perish before the Armistice in 1918.

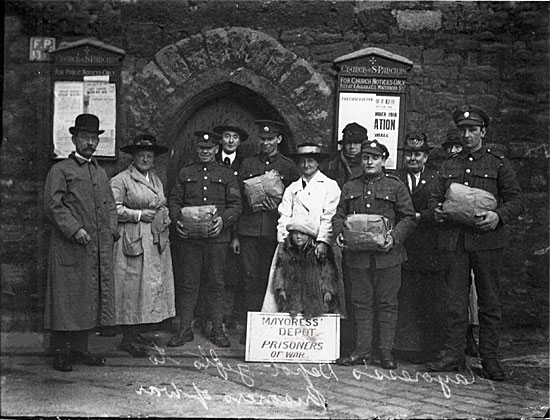

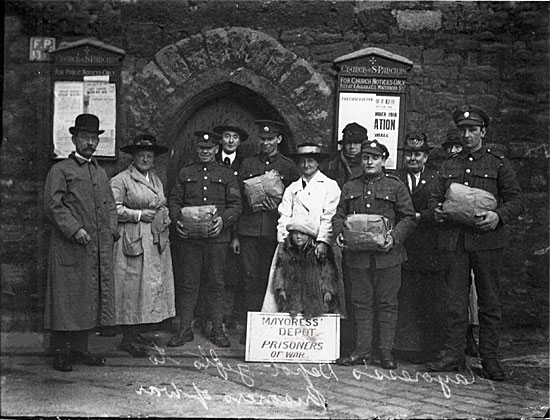

Apart from the many voluntary hospitals and convalescent homes in the city, many Belgian refugees were welcomed into local homes. Mrs J.G. Owen, the Mayoress, worked tirelessly on multiple schemes to relieve need and, early in 1917, the EOS Committee resolved that “profits of this year’s festival (be given) to the Mayoress of Exeter’s Fund earmarked to Prisoners of War.”

The Mayoress, Mrs J.G. Owen and helpers outside St Pancras Church, 1917

(Image supplied through ‘Exeter Memories’ by kind permission of David Cornforth)

Peacetime returns

While 1918 was to see a decisive step toward victory on the battlefield, in Exeter severe flooding of the Exe was followed by heavy snowfall. Then, as summer approached, the city was swept by the influenza pandemic, with forty-two fatalities reported in Exeter itself. As the disease began to subside the Great War finally came to an end with the signing of the Armistice on 11 November.

Victoria Hall fire, October 1919 (Image supplied through 'Exeter Memories' by kind permission

of David Cornforth)

After the destruction by fire of Victoria Hall, the society’s usual concert venue, along with its fine Willis organ, the EOS was without a home for its 1919 concert. With two weeks to go, the Dean and Chapter of Exeter Cathedral gave permission for the use of the Cathedral as a performance venue. This happy outcome may well have had something to do with the appointment of Ernest Bullock as the Society’s conductor earlier in the year. Bullock, who had served as a Captain in the First World War, became organist and choir master at the Cathedral on his return from the army.

“A most successful concert”

By 1919, despite the effect of wartime on the Society’s musicians and their ability to make music, “band and chorus”, as one critic put it, numbered 500. Notwithstanding the change of venue, the 1919 Annual Festival of the Exeter Oratorio Society was, declared the Devon & Exeter Daily Gazette, “one of the most successful in the history of the Society”. Two concerts were given, one in the afternoon and one in the evening of 22 October 1919, to a packed audience. Both included the first public performance of a special composition by Devon composer, Dr H. J. Edwards. His Hymn of Victory and Peace marked the “victorious termination of hostilities”, coming as the Treaty of Versailles awaited ratification.

Both performances featured pieces that today’s singers would recognise – selections from Handel’s Messiah (including “And the Glory of the Lord”) and Parry’s Blest Pair of Sirens. Alongside Mendelssohn’s symphonic cantata, Hymn of Praise, and Sullivan’s overture, In Memoriam, the centrepiece was Edwards Hymn of Victory and Peace, which the composer himself conducted. The Gazette pronounced it a “brilliant performance” of the “gem” of the festival, “a composition which will appeal to all lovers of music”.

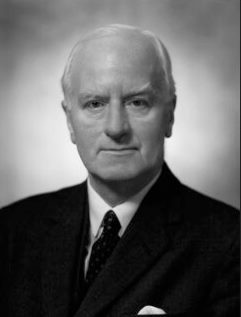

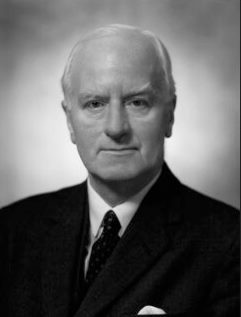

Sir Ernest Bullock, 1890-1970 [Image 1960, National Portrait Gallery, Bassano)

Aged twenty-nine on his appointment, Bullock was known for his determination to put new life into the music of the Cathedral and the city, including EOS. He later became organist and master of the choristers at Westminster Abbey and, with the same energy he showed in Exeter, was responsible for the music at the coronation of George VI in May 1937. A distinguished composer of church music, he was later knighted.

In 1930, the EOS merged again, this time with the Cathedral Augmented Choir to form the Exeter Musical Society (EMS). During this time, a second Cathedral organist and choir master, Sir Thomas Armstrong, became the conductor of the new EMS (until 1933). He was succeeded by Dr Alfred Wilcock, who had also been appointed Cathedral Organist by the Dean and Chapter. The connection between the Cathedral and the Society would only strengthen over time, particularly through the turbulence of a second world war.

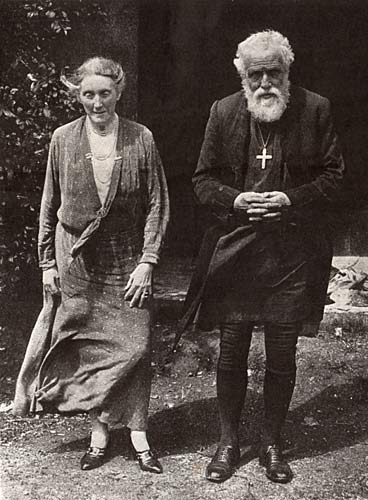

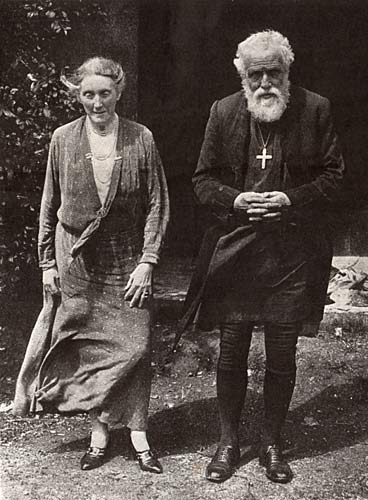

In 1936, the Bishop of Exeter, Lord William Cecil, died, having been a key figure in the Cathedral, City and diocese since his appointment. A kind and tolerant man, he was noted for his eccentricity and “administrative ineptitude”. He and his wife never recovered from the loss of three of their four sons killed in the Great War: the fourth, though wounded twice, survived.

Bishop Lord William Cecil and Lady Florence

(Image supplied through 'Exeter Memories' by kind permission of David Cornforth)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

War and the choir’s darkest hour

In 1939, war was once more upon the country.

In September 1940, the German air force, the Luftwaffe, began a sustained campaign of bombing on British towns and cities, notably London itself. Strategic targets in the South of England were also attacked, including Bristol, Southampton, Plymouth and Portsmouth. In 1942, in retaliation for the RAF’s bombing of Lübeck, the Germans directed their attention to cities of historic or cultural importance, as featured in Baedeker’s authoritative guide book to Great Britain.

The prelude to the Exeter “Baedeker blitz” came in April 1942, with several German air raids. There was some loss of life and injury and hundreds of houses were damaged but nothing on the scale of what was to come at the beginning of May. Even so, the military historian and writer, Charles Whiting, claimed that following the raids some of Exeter’s citizens advocated dynamiting the Cathedral to prevent it being used as a target and as a guide for German bombers attacking the city. The fact that the preferred solution would also have had the effect of attaining the Luftwaffe’s primary objective was not mentioned.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Exeter Blitz

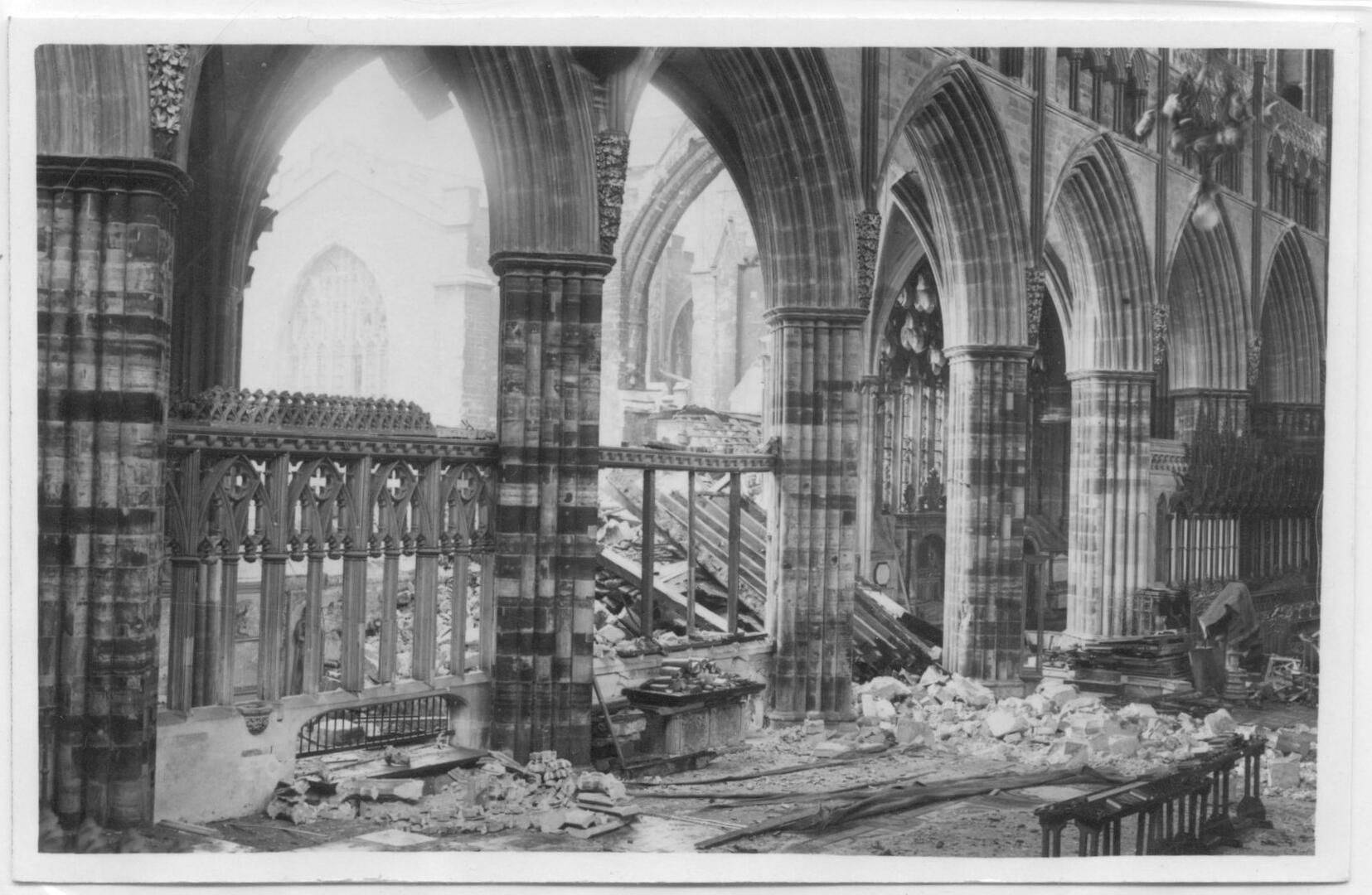

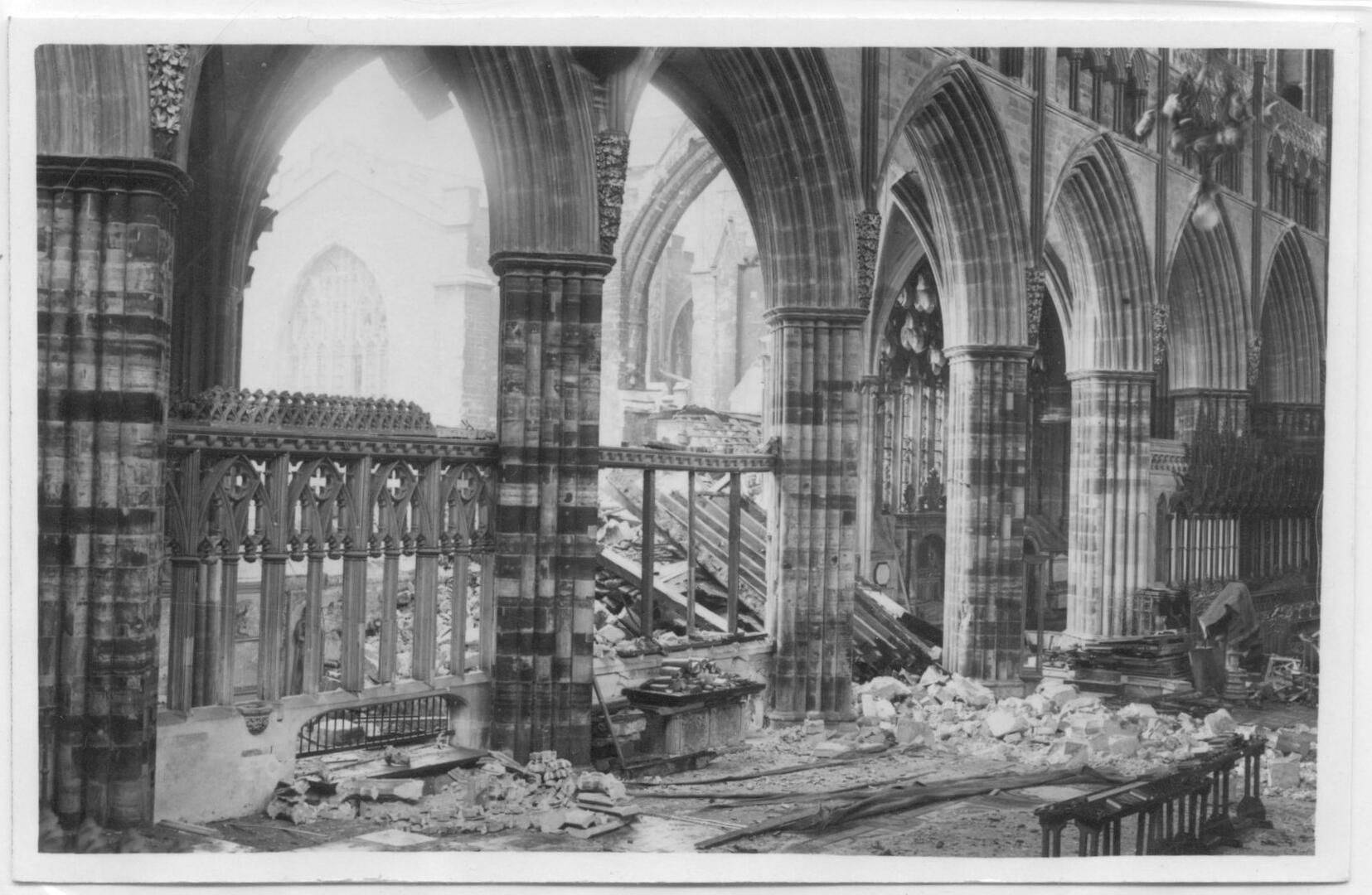

It was just after midnight on 4 May 1942. Twenty German bombers arrived over the largely undefended city of Exeter and, in seventy minutes of bombing and strafing, devastated much of the city centre. 156 people were killed and 583 injured. The fires burnt for days before being finally extinguished. Nearly a quarter of Exeter’s 20,000 houses were obliterated or badly damaged, as well as offices, business, shops and pubs. While the Cathedral suffered only limited damage – a high explosive bomb destroying the Chapel of St James – the City Library was flattened, with the loss of one million documents and books. Many historic buildings were lost. The following day, German radio declared that England’s “jewel of the West” had been destroyed. It was “Exeter’s Crucifixion”, declared the Western Morning Mail. More precisely, Sir Nikolaus Pevsner later remarked: “The Germans found Exeter primarily a medieval city; they left it primarily a Georgian and early Victorian city.”

Interior damage to Exeter Cathedral, 1942 (Courtesy Exeter Cathedral)

The fires that ravaged thirty acres of the city centre, and many of its remaining medieval buildings, also gutted most of Bedford Circus, widely recognised as an exceptional example of Georgian town planning. No. 8 Bedford Circus, the home of the Secretary of the Exeter Musical Society, was not spared and into the conflagration went nearly all the Society’s records (though most of its money had been safely banked). The Choristers School, including the Headmaster’s house, was badly damaged and the Hall of the Vicars Choral College was also destroyed. While there was some loss of life (including one of the Headmaster’s daughters and three domestic servants), most of the staff and choristers were away, it being the holidays. The BBC correspondent, Frank Gillard, later reported that following the attack he had heard a woman singing at the top of her voice as she swept the pavement of broken glass.

Firefighters in the High Street, tackling the blaze at Colsons, with a destroyed Deller’s Cafe behind (Image courtesy of Express & Echo)

In the aftermath of the devastation, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth visited the ravaged city on 8 May as part of a West Country tour. British Pathe news reported that: “the King and Queen met bombed townsfolk as old campaigners of the London Blitz”.

A little over a month later, on 10 June, an informal meeting of EMS, called by newspaper advertisement, assembled in St Petrock’s Church “to test the feeling of the members, regarding the resumption of rehearsals, owing to the devastated condition of the City”. The first thought of those present was for the Choristers School and its headmaster, Revd. Langhorne, and “to those of the City generally who suffered bereavement, pain and distress”.

The future was uncertain. Apart from the May blitz, there had been other air raids and Hitler had promised that his Luftwaffe would return “to finish the job”. There were also many practical problems. The Cathedral, for the foreseeable future, could not be used for performances, nor could rehearsals be held in the Chapter House, which had also been damaged. The Cathedral organ had been put out of action and, coincidentally, all EMS’s music stands had been lost. Nevertheless, the minutes of the meeting recorded that as regards the central issue before the meeting there was “a wonderful response” and it was agreed that rehearsals would resume in two weeks, on 24 June at the usual time, at St Petrock’s Church. With optimism overflowing, the meeting expressed the hope “that the Cathedral would be ready for an early autumn performance of “The Messiah”, under the baton of Dr Alfred Wilcock, the Society’s conductor.

Choristers in the ruins of the Choir School, Exeter, 1942

(Keith Gibb, Photographic archive Vol 2)

Unsurprisingly, this proved a little over-optimistic, perhaps fuelled by “the goodly measure of friendly feeling” at the meeting, which the Secretary had noted in the minutes. Nevertheless, when the EMS Committee met in October, it was agreed that the concert would instead take place at 2.30 pm on Saturday 28 November at the Mint Methodist Church, by kind permission of the Minister, Revd. Whitehead. Admission tickets would be sent to subscribers as usual, and seats reserved until fifteen minutes before the start of the performance. Since this was to be a choral rendition of Messiah without the orchestra, arrangements were also made to use the Mint’s organ.

Dr Wilcock later declared that, taking into consideration the “present difficult times”, the performance at the Mint had been “very satisfactory”, adding that he himself was “quite pleased”. At such very short notice, the choir had been without an organist, but Dr Wilcock found J. M. Hind, FRCO, a Cathedral relief organist who was at that moment on leave from the army and who agreed to play, “accompanying the whole work beautifully”. A letter of appreciation and three guineas followed.

Visit of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth to bomb-damaged Exeter, 1942

(Image supplied through ‘Exeter Memories’ by kind permission of David Cornforth)

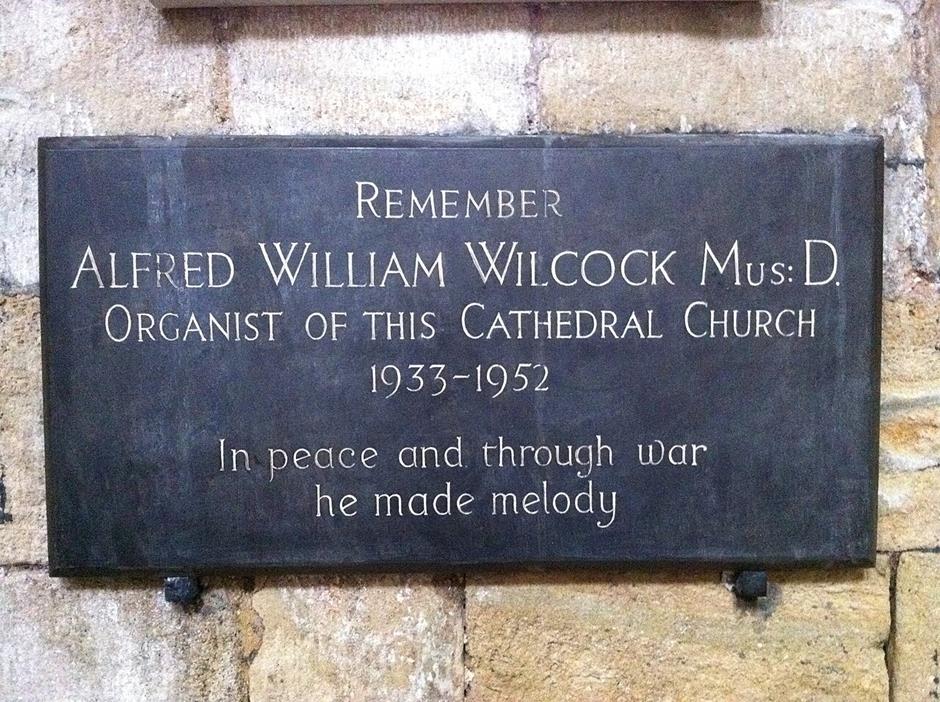

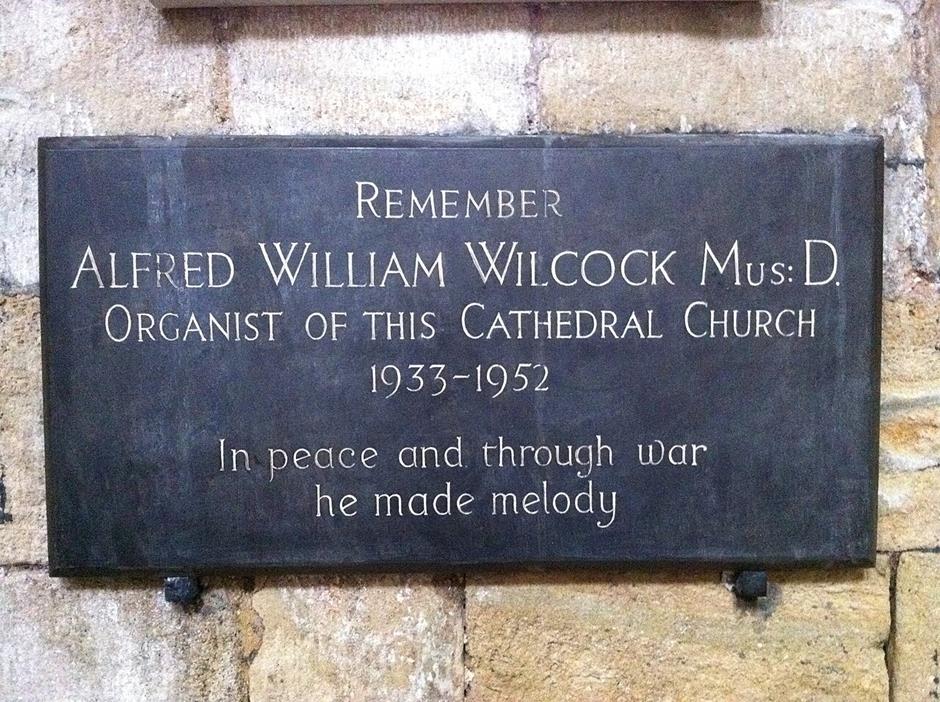

By the start of January 1943, planning had begun for the EMS’s next concert, to be held in April. The Chapter House had been repaired and was now available for rehearsals. Dr Wilcock proposed Haydn’s Creation as a suitable work, adding that “something more prodigious would have to be left until after the war”. This suggestion was met with general approval, although the minutes recorded that “one or two members would have liked a more progressive programme”. This, the Secretary recorded, “showed that the Society was alive in spite of war and depression”. This sentiment is captured by Dr Wilcock’s memorial in Exeter Cathedral, where he was the organist from 1933 until 1952. The simple epitaph reads: “In peace and through war he made melody.”

Memorial to Alfred William Wilcock (1887-1953), Exeter Cathedral

(Image courtesy of Andrew Abbott, 5 June 2011)

The Blitz Window, Exeter Cathedral (Courtesy Exeter Cathedral)

The post-war period – choir and community rebuild

(under construction)

The Royal Subscription Rooms, Exeter, the location of the choir’s first performance in 1847 (Image supplied through ‘Exeter Memories’ by kind permission of David Cornforth)

The Exeter Philharmonic Choir is one of the oldest amateur choral societies in the UK. Founded in 1846, early in the reign of Queen Victoria, it had its beginnings in the formation of the Exeter Oratorio Society (EOS). On 22 October 1846, twenty-two Cathedral singers and local musicians (elsewhere described as “a party of Vicars Choral and Exeter Gentlemen”) gathered in “Mr Risdon’s room” in Exeter to set the wheels on motion. A week later, a general meeting with around forty present agreed that “the primary object of this Society be the encouragement of Oratorios, Anthems and the higher branches of Sacred Music in General”. Composed of both singers and instrumentalists, the new society prepared for its first concert – a performance of Handel’s Messiah in Easter Week 1847, at the Royal Subscription Rooms on Exeter’s now vanished London Inn Square. Until that moment, the Society’s membership had been resolutely male but that was soon to change. (For more about women in the Society, click here).

Cholera, Dr Thomas Shapter (and choral music)

Cholera, Dr Thomas Shapter (and choral music)

Around a decade before the formation of the Exeter Oratorio Society, Exeter had been struck by a serious outbreak of cholera. The first victim of the disease was a mother (with two sick children) living in North Street. By the time the outbreak had been contained, there had been 1,200 cases and 402 fatalities. A young medical doctor, Thomas Shapter, offered his services to the Board of Health, working tirelessly with those affected but also recording and mapping the impact of the disease and the insanitary living conditions on which it thrived. In an Open Letter to Exeter’s Lord Mayor, Shapter speculated that “lack of ventilation, overcrowding and squalor” were to blame, with his voice contributing to the clamour for the adoption of new public health legislation in 1848.

Thomas Shapter’s cholera map of Exeter, 1832 (Engraving by Risdon, Lith., Exeter in

Shapter, Thomas History of the Cholera in Exeter 1832 John Churchill, 1849)

Whether or not the founding members of the EOS also considered the public health benefits of music and singing, the Society’s first performance took place on Maundy Thursday 1847 at the Subscription Rooms. An EOS notice declared that “all the Members will be required to take their respective parts. No free admissions will be granted.” Prices were “2/6d entry and Reserved Seats 4/-”, but such was the demand for seats on the day that tickets were sold “at a guinea apiece”. The concert was pronounced a success, both in terms of the large and enthusiastic audience that attended and the much-needed funds raised to help the new society buy music and equipment as it established itself. The correspondent of The Western Times reported that: “Forty instruments, and one hundred and twenty vocalists, raised a swell of harmony such as was never before heard within the ancient jurisdiction of the faithful old city.”

Dr Thomas Shapter, eminent physician and member of EOS (Portrait of Thomas Shapter

in the Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital, Wellcome Gallery, London, artist unknown)

Among the ranks of the basses was Dr Thomas Shapter, newly appointed as a physician at the Devon & Exeter Hospital and about to publish his acclaimed book on the Exeter cholera outbreak. Joining the alto voices was W. Denis Moore, the Lord Mayor of Exeter, whose presence, The Western Times reported, was greeted with “hearty and protracted applause”.

However, on 20 May 1847, the Committee reported that “a communication had been received from the Right Worshipful the Lord Mayor requesting that a second performance of the Messiah might be given for the purpose of increasing the funds now in collection for the relief of the poor.” The Committee duly agreed and arranged a second performance on the same basis as before. At a General Meeting of the Society after the concert, on 1 July, there was a marked change of mood. It was “Resolved – That the balance of £39.00 be paid to the Treasurer of the Relief Fund” (worth around £5,000 at 2024 prices). Parting with this amount of money was clearly a painful experience and the meeting added a rider: “That in future no performances were to be given on behalf of any charities.”

The following year Dr Thomas Shapter himself became Lord Mayor and relations between the EOS and Exeter’s mayoralty seem to have improved. For many years, Dr Shapter played a considerable part in the life of the Society, which resumed the practice of performing for charity.

Discordant notes

By 1850, there were signs that some of the EOS’s early enthusiasm was being tempered by reality. Handel’s Messiah remained a standard part of the repertoire, though Haydn’s Creation was selected for the spring public performance in 1849. While the Annual Report the next year reported that the Messiah choruses were performed by the Society’s choir “with a better observance of light and shade than hitherto”, the Committee impressed on the membership the importance of regular attendance at rehearsals. Only by “regular and simultaneous practice” could the choir hope to develop a full understanding of the compositions. As it was, the Committee considered that “there is wanting a greater power of expression, a better observance of the various gradations of tone, and distinct pronunciation of the words – all necessary to the clear effectual development of the Composer’s meaning.”

The Committee acknowledged that the membership was pressing to perform works by Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Mendelssohn and Spohr but warned that “although much has been done, still they cannot but feel that a great advance must take place before the works of these Writers can be attempted with success.”

An extract from the Minute Book, 1850 [Devon Heritage Centre, Devon archives:

Exeter Oratorio Society. Minute Book 1846 – 1859, 219/48/4)

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

A new monarch – and a new century

By the turn of the century, the Exeter Oratorio Society had successfully navigated its first fifty years and was an established part of musical life in Exeter. In 1901, Queen Victoria died at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight at the age of eighty-one, having reigned for sixty-three years (longer than any of her predecessors). Her eldest son “Bertie” at last succeeded to the throne as Edward VII. His coronation in 1902 was widely celebrated, including in Exeter where the “musical societies”, as the programme records, played their part in the festivities.

The Exeter Coronation celebrations, 1902 (first day)

Image supplied through 'Exeter Memories' by kind permission of David Cornforth

In 1906, the Society marked its first sixty years with the publication of a commemorative booklet. A year later it merged with the Western Counties Musical Association, appointing joint conductors until 1919. In 1913, in the Victoria Hall, the society performed Handel’s Samson in the afternoon, and H. J. Edward’s Ascension and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s A Tale of Old Japan in the evening. Performing twice in a day, and presenting separate repertoires, was a common pattern at the time but must have been challenging, both physically and technically.

EOS programme for April 1913 concerts (Archive of Exeter Philharmonic Choir)

Caroline Hatchard at Exeter

Prominent among the soloists for the two concerts on 2 April 1913 was the celebrated soprano, Miss Caroline Hatchard. Aged thirty, she was approaching the height of her powers. (For more about Caroline Hatchard, click here).

The Great War comes to Exeter

On 4 August 1914, Great Britain was at war, the news breaking in Exeter from the offices of The Western Times in the High Street. The improbable spark to what became a world-wide conflagration was the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, together with his wife, in Sarajevo. The interlocking alliances of the great powers, which were supposed to guarantee peace, instead made war inevitable. Two days later, one of the first official fatalities of ‘The Great War’ was Stoker Henry Copland, from Topsham. He was killed when his ship, HMS Amphion, struck a German mine in the Thames estuary and quickly sank, with much loss of life.

The Devon Reserves parade down Exeter High Street, 7 August 1914

(Image supplied through ‘Exeter Memories’ by kind permission of David Cornforth)

Amid great patriotic fervour, reservists and territorials were mobilised and many answered Field Marshal Kitchener’s appeal to join the colours as he built new volunteer forces to augment Britain’s small professional army. Commonwealth forces also began to pass through Exeter on their way to France and other battlefields. By Christmas 1914, the festivities at home continued much as before, with “Mother Goose” the pantomime at the Theatre Royal. The Exeter Oratorio Society had selected Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius as the highlight of its 1914 festival but “having regard to the War they were reluctantly compelled to postpone its performance”. Nevertheless, EOS’s concerts continued throughout hostilities, though The Gazette reported that “they had suffered somewhat by the depletion in the ranks of male voices”.

By 1916, two major battles – one at sea and one at land – saw many from Exeter and Devon featuring on the casualty lists. At the Battle of Jutland, which narrowly confirmed

Britain’s naval supremacy, twenty-six sailors from Exeter died in battle. The youngest was Aaron Balson, of Bartholomew Street, Exeter, who was just eighteen.

A month after Jutland, British and Commonwealth forces, together with the French Army, launched a major offensive which became known as the Battle of the Somme. At the end of the first day, allied forces had sustained 57,000 casualties, with nearly 20,000 killed. Of the dead, twenty-two were from Exeter. Only modest advances in the frontline were achieved over four months of fighting.

The mounting death toll showed itself in numerous personal tragedies and broken families. The new Bishop of Exeter, Lord William Gascoyne-Cecil, took office in December 1916. By then, he had already lost one of his four sons, aged twenty, at Ypres the year before. Two more of his sons were to perish before the Armistice in 1918.

Apart from the many voluntary hospitals and convalescent homes in the city, many Belgian refugees were welcomed into local homes. Mrs J.G. Owen, the Mayoress, worked tirelessly on multiple schemes to relieve need and, early in 1917, the EOS Committee resolved that “profits of this year’s festival (be given) to the Mayoress of Exeter’s Fund earmarked to Prisoners of War.”

The Mayoress, Mrs J.G. Owen and helpers outside St Pancras Church, 1917

(Image supplied through ‘Exeter Memories’ by kind permission of David Cornforth)

Peacetime returns

While 1918 was to see a decisive step toward victory on the battlefield, in Exeter severe flooding of the Exe was followed by heavy snowfall. Then, as summer approached, the city was swept by the influenza pandemic, with forty-two fatalities reported in Exeter itself. As the disease began to subside the Great War finally came to an end with the signing of the Armistice on 11 November.

Victoria Hall fire, October 1919 (Image supplied through 'Exeter Memories' by kind permission

of David Cornforth)

After the destruction by fire of Victoria Hall, the society’s usual concert venue, along with its fine Willis organ, the EOS was without a home for its 1919 concert. With two weeks to go, the Dean and Chapter of Exeter Cathedral gave permission for the use of the Cathedral as a performance venue. This happy outcome may well have had something to do with the appointment of Ernest Bullock as the Society’s conductor earlier in the year. Bullock, who had served as a Captain in the First World War, became organist and choir master at the Cathedral on his return from the army.

“A most successful concert”

By 1919, despite the effect of wartime on the Society’s musicians and their ability to make music, “band and chorus”, as one critic put it, numbered 500. Notwithstanding the change of venue, the 1919 Annual Festival of the Exeter Oratorio Society was, declared the Devon & Exeter Daily Gazette, “one of the most successful in the history of the Society”. Two concerts were given, one in the afternoon and one in the evening of 22 October 1919, to a packed audience. Both included the first public performance of a special composition by Devon composer, Dr H. J. Edwards. His Hymn of Victory and Peace marked the “victorious termination of hostilities”, coming as the Treaty of Versailles awaited ratification.

Both performances featured pieces that today’s singers would recognise – selections from Handel’s Messiah (including “And the Glory of the Lord”) and Parry’s Blest Pair of Sirens. Alongside Mendelssohn’s symphonic cantata, Hymn of Praise, and Sullivan’s overture, In Memoriam, the centrepiece was Edwards Hymn of Victory and Peace, which the composer himself conducted. The Gazette pronounced it a “brilliant performance” of the “gem” of the festival, “a composition which will appeal to all lovers of music”.

Sir Ernest Bullock, 1890-1970 [Image 1960, National Portrait Gallery, Bassano)

Aged twenty-nine on his appointment, Bullock was known for his determination to put new life into the music of the Cathedral and the city, including EOS. He later became organist and master of the choristers at Westminster Abbey and, with the same energy he showed in Exeter, was responsible for the music at the coronation of George VI in May 1937. A distinguished composer of church music, he was later knighted.

In 1930, the EOS merged again, this time with the Cathedral Augmented Choir to form the Exeter Musical Society (EMS). During this time, a second Cathedral organist and choir master, Sir Thomas Armstrong, became the conductor of the new EMS (until 1933). He was succeeded by Dr Alfred Wilcock, who had also been appointed Cathedral Organist by the Dean and Chapter. The connection between the Cathedral and the Society would only strengthen over time, particularly through the turbulence of a second world war.

In 1936, the Bishop of Exeter, Lord William Cecil, died, having been a key figure in the Cathedral, City and diocese since his appointment. A kind and tolerant man, he was noted for his eccentricity and “administrative ineptitude”. He and his wife never recovered from the loss of three of their four sons killed in the Great War: the fourth, though wounded twice, survived.

Bishop Lord William Cecil and Lady Florence

(Image supplied through 'Exeter Memories' by kind permission of David Cornforth)

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

War and the choir’s darkest hour

In 1939, war was once more upon the country.

In September 1940, the German air force, the Luftwaffe, began a sustained campaign of bombing on British towns and cities, notably London itself. Strategic targets in the South of England were also attacked, including Bristol, Southampton, Plymouth and Portsmouth. In 1942, in retaliation for the RAF’s bombing of Lübeck, the Germans directed their attention to cities of historic or cultural importance, as featured in Baedeker’s authoritative guide book to Great Britain.

The prelude to the Exeter “Baedeker blitz” came in April 1942, with several German air raids. There was some loss of life and injury and hundreds of houses were damaged but nothing on the scale of what was to come at the beginning of May. Even so, the military historian and writer, Charles Whiting, claimed that following the raids some of Exeter’s citizens advocated dynamiting the Cathedral to prevent it being used as a target and as a guide for German bombers attacking the city. The fact that the preferred solution would also have had the effect of attaining the Luftwaffe’s primary objective was not mentioned.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Exeter Blitz

It was just after midnight on 4 May 1942. Twenty German bombers arrived over the largely undefended city of Exeter and, in seventy minutes of bombing and strafing, devastated much of the city centre. 156 people were killed and 583 injured. The fires burnt for days before being finally extinguished. Nearly a quarter of Exeter’s 20,000 houses were obliterated or badly damaged, as well as offices, business, shops and pubs. While the Cathedral suffered only limited damage – a high explosive bomb destroying the Chapel of St James – the City Library was flattened, with the loss of one million documents and books. Many historic buildings were lost. The following day, German radio declared that England’s “jewel of the West” had been destroyed. It was “Exeter’s Crucifixion”, declared the Western Morning Mail. More precisely, Sir Nikolaus Pevsner later remarked: “The Germans found Exeter primarily a medieval city; they left it primarily a Georgian and early Victorian city.”

Interior damage to Exeter Cathedral, 1942 (Courtesy Exeter Cathedral)

The fires that ravaged thirty acres of the city centre, and many of its remaining medieval buildings, also gutted most of Bedford Circus, widely recognised as an exceptional example of Georgian town planning. No. 8 Bedford Circus, the home of the Secretary of the Exeter Musical Society, was not spared and into the conflagration went nearly all the Society’s records (though most of its money had been safely banked). The Choristers School, including the Headmaster’s house, was badly damaged and the Hall of the Vicars Choral College was also destroyed. While there was some loss of life (including one of the Headmaster’s daughters and three domestic servants), most of the staff and choristers were away, it being the holidays. The BBC correspondent, Frank Gillard, later reported that following the attack he had heard a woman singing at the top of her voice as she swept the pavement of broken glass.

Firefighters in the High Street, tackling the blaze at Colsons, with a destroyed Deller’s Cafe behind (Image courtesy of Express & Echo)

In the aftermath of the devastation, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth visited the ravaged city on 8 May as part of a West Country tour. British Pathe news reported that: “the King and Queen met bombed townsfolk as old campaigners of the London Blitz”.

A little over a month later, on 10 June, an informal meeting of EMS, called by newspaper advertisement, assembled in St Petrock’s Church “to test the feeling of the members, regarding the resumption of rehearsals, owing to the devastated condition of the City”. The first thought of those present was for the Choristers School and its headmaster, Revd. Langhorne, and “to those of the City generally who suffered bereavement, pain and distress”.

The future was uncertain. Apart from the May blitz, there had been other air raids and Hitler had promised that his Luftwaffe would return “to finish the job”. There were also many practical problems. The Cathedral, for the foreseeable future, could not be used for performances, nor could rehearsals be held in the Chapter House, which had also been damaged. The Cathedral organ had been put out of action and, coincidentally, all EMS’s music stands had been lost. Nevertheless, the minutes of the meeting recorded that as regards the central issue before the meeting there was “a wonderful response” and it was agreed that rehearsals would resume in two weeks, on 24 June at the usual time, at St Petrock’s Church. With optimism overflowing, the meeting expressed the hope “that the Cathedral would be ready for an early autumn performance of “The Messiah”, under the baton of Dr Alfred Wilcock, the Society’s conductor.

Choristers in the ruins of the Choir School, Exeter, 1942

(Keith Gibb, Photographic archive Vol 2)

Unsurprisingly, this proved a little over-optimistic, perhaps fuelled by “the goodly measure of friendly feeling” at the meeting, which the Secretary had noted in the minutes. Nevertheless, when the EMS Committee met in October, it was agreed that the concert would instead take place at 2.30 pm on Saturday 28 November at the Mint Methodist Church, by kind permission of the Minister, Revd. Whitehead. Admission tickets would be sent to subscribers as usual, and seats reserved until fifteen minutes before the start of the performance. Since this was to be a choral rendition of Messiah without the orchestra, arrangements were also made to use the Mint’s organ.

Dr Wilcock later declared that, taking into consideration the “present difficult times”, the performance at the Mint had been “very satisfactory”, adding that he himself was “quite pleased”. At such very short notice, the choir had been without an organist, but Dr Wilcock found J. M. Hind, FRCO, a Cathedral relief organist who was at that moment on leave from the army and who agreed to play, “accompanying the whole work beautifully”. A letter of appreciation and three guineas followed.

Visit of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth to bomb-damaged Exeter, 1942

(Image supplied through ‘Exeter Memories’ by kind permission of David Cornforth)

By the start of January 1943, planning had begun for the EMS’s next concert, to be held in April. The Chapter House had been repaired and was now available for rehearsals. Dr Wilcock proposed Haydn’s Creation as a suitable work, adding that “something more prodigious would have to be left until after the war”. This suggestion was met with general approval, although the minutes recorded that “one or two members would have liked a more progressive programme”. This, the Secretary recorded, “showed that the Society was alive in spite of war and depression”. This sentiment is captured by Dr Wilcock’s memorial in Exeter Cathedral, where he was the organist from 1933 until 1952. The simple epitaph reads: “In peace and through war he made melody.”

Memorial to Alfred William Wilcock (1887-1953), Exeter Cathedral

(Image courtesy of Andrew Abbott, 5 June 2011)

The Blitz Window, Exeter Cathedral (Courtesy Exeter Cathedral)

The post-war period – choir and community rebuild

(under construction)